Everything Was Always Better

Hand Craft in Contemporary Art

Barbora Hájková

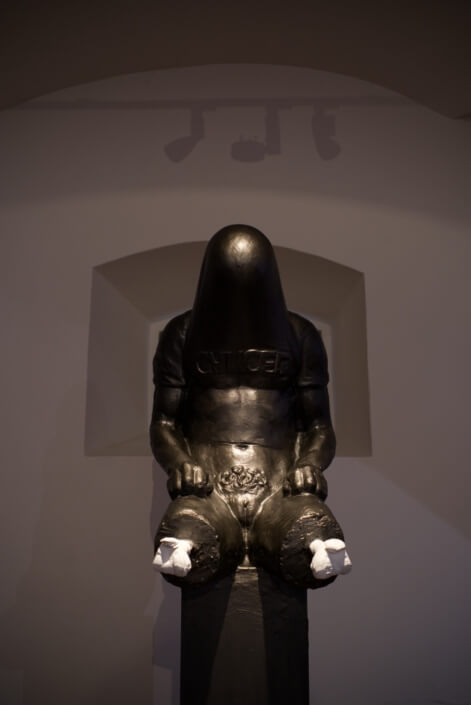

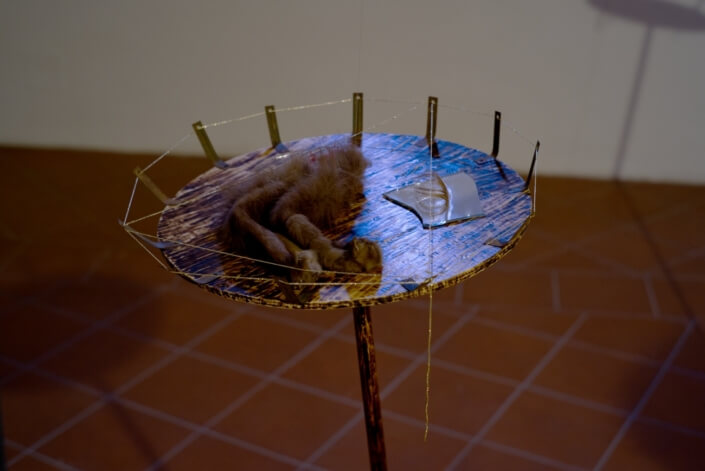

The artists participating in the Everything Was Always Better exhibition are connected particularly by their approach to the production of works. In simple terms, they make them with their hands. During the creation of the work, they arrive at the limits of the technical possibilities of the materials and craft technologies they use. Karíma Al-Mukhtarová, Matouš Háša, Tomáš Kurečka, and Martin Pondělíček can be considered as part of the young generation of artists who came of age and established themselves on the art scene during the years of post-socialist transformation. Although in many ways the Czech Republic is gradually integrating into the European (Western) form of cultural thinking, the use and development of hand crafts, or handicraft, was different on each side of the Iron Curtain. The following text therefore attempts a comparison of approaches to handicrafts in both the Western and Eastern “cubes”. (These terms are from Tomáš Pospiszyl’s book Srovnávací studie (Comparative Studies, Fra, 2005), in which he describes the varied development of modernist art divided by the Iron Curtain. I use these terms both in the context of the development of art in the second half of the 20th century and the period of post-socialist transformation.)

In Czechoslovakia, during the period known as the Prague Spring, and particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, there was great interest in DIY (do it yourself) – the creation of both practical and aesthetic objects with one’s own hands. There were several reasons for this phenomenon. Primarily, it developed as a response to the fact that many products were unavailable for purchase. The population’s desire for original and design products often led to the creation of obscure objects, but the phrase “Golden Czech hands” is linked directly to the period known as normalisation (which took place in the 1970s and 1980s, following the Warsaw Pact invasion that ended the Prague Spring in 1968).

The DIY phenomenon was also crucial in providing a way for people to spend their time. In a study for the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, sociologist Petr Gibas has explored the deeper roots of this phenomenon, which stretches back to the turn of the 20th century, across the geopolitical divide. He finds the primary reason for the rise in interest in handicraft and DIY in Europe and North America in the growing economic and gender freedom of the middle classes (with urban society developing in a different way to the countryside). Related to these developments is the establishment of the Arts and Crafts movement during the late 19th century, which had a strong social and reforming focus, particularly in relation to a critique of patriarchy.

Handicraft, however, is typical of human activity (including artistic activity) from the dawn of time. The artefacts that survive from our prehistoric ancestors include work tools used to provide food and essential needs, as well as objects probably used for rituals, which also had – unlike everyday tools – a spiritual dimension. Both the general public and experts consider these “cultural” objects one of the most significant areas of our spiritual heritage. Let us think, for instance, of zoomorphic carvings, Venus statuettes, or Neolithic fetishes. Celebrated anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss links hand craft used to create “artistic” objects with mythical thinking. From this, we can extrapolate the idea that contemporary artists who reflect this principle in their work define themselves against purely rational modes of thought. All of the artists participating in this exhibition project personal reminiscences into their work. They draw inspiration from social and cultural phenomena, but their works are concerned primarily with questions of identity.

The development of contemporary art in Western countries, linked to the treatment of natural and easily accessible (cheap) materials and the use of traditional techniques in object creation, relates to the rise of the Italian Arte Povera movement in the late 1960s. This was a modernist approach that nevertheless also influenced later developments in conceptual art. German artist Joseph Beuys also made use of unusual materials often (felt, honey, wax, fat). In the 1960s, he abandoned modernist tradition and developed his own conception of an “extended definition of art”, in which he ascribes to art a central position in the process of extricating society from its cultural, economic, and social crises. His work and life were influenced by various themes, including humanism, ecology, sociology, and, especially, anthroposophy, an esoteric teaching founded by Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophy is concerned with mystical insight into the essence of the human being. The social movement known as craftivism follows in the footsteps both of the Arts and Crafts movement and of Joseph Beuys’s approach. It was established at the beginning of the 21st century and mostly makes use of embroidery and other techniques commonly connected to the feminine role.

In the late 1990s, Jana and Jiří Ševčík reflected (from a curatorial and theoretical perspective) on certain tendencies related to the search for identity and object creation on the Czech art scene. In particular, their 1997 exhibition in the Mánes Gallery, Snížený rozpočet (Docked Budget), focused directly on this more intimate form of artistic expression. In the context of recent Czech art history, we must also mention those figures who, during the first decade of the new millennium, came to be known as “Insiders”, following a curatorial and theoretical contextualisation by Pavlína Morganová: “The curator highlights the ‘insider’ operation of the art scene whilst also attempting to delineate the work of the ‘young’ artists based on shared formal characteristics. The element meant to connect the ‘inconspicuous generation’ was ‘handcraft dexterity and cheap materials – a kind of ‘noble DIY’.” (A summary of Pavlína Morganová’s lecture on Artyčok.tv also states that some artists criticised their inclusion in this stylistic description. But artists focusing mostly on object creation – such as Michal Pěchouček – certainly made use of craft-based principles in their work.)

The works exhibited in the Everything was always better express the personal and intimate statements of the artists, but they also open deeper societal questions in the context of contemporary thinking about art – e.g. the perception of temporality in our technology-dominated era, or gender stereotypes related to manual creative activity. The exhibition therefore captures the human situation in a broader social, historical, and cultural context.

Translation: Ian Miskyska

Photo: Marie Sieberová

Graphic design: Josef Čevora

Everything Was Always Better

Karíma Al-Mukhtarová, Matouš Háša, Tomáš Kurečka, Martin Pondělíček

Pardubice City Gallery

20. 1. – 7. 3. 2021

Curators: Daniela Kramerová and Barbora Hájková